Director: Agnès Varda

Country: France

This is a particularly special entry for this still-young blog. Not only is it the first featured film from France (a country with a ridiculously rich cinematic heritage) and the first film from the French New Wave, but it is also a much-loved favorite of mine which, like Fellini's

8 1/2, helped introduce me to the wonders and delights of the European art cinema of the 1960s.

Cléo was actually chosen as a prime example of the European art film for my 2nd year Film History class in an essay question which asked me to analyze the film and write about its historical significance. I had been meaning to see it before that assignment, but the resulting essay was a wonderful way of discovering this sparkling gem of French cinema, and I've been a strong fan of it and Varda ever since.

While

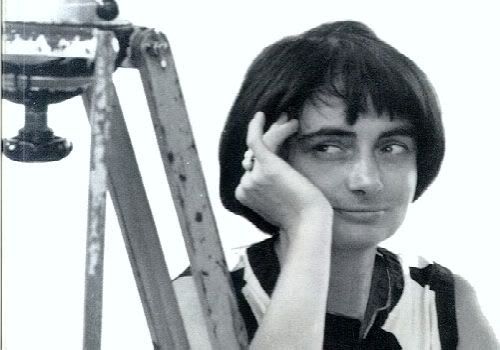

Cléo From 5 to 7 quite ably stands on its own as a great film, something should be said about the unique situation of its author. Agnès Varda is widely known as the "godmother" or "grandmother" of the French New Wave and was one of the few women (and certainly the best-known one) who successfully infiltrated the boy's club of the French New Wave group, which of course included the Cahiers du Cinema comrades François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Chaude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette. However, she stands somewhat apart from them in a few ways. She is more specifically associated with the Left Bank group of filmmakers who arrived onto the French film scene during the New Wave. They weren't as cinema-crazy as the Cahiers group, instead drawing from other art forms such as painting and photography (Varda herself was a photographer before making her first film,

La Pointe courte). Along with Varda, the other main Left Bank figures are Alain Resnais (

Hiroshima, Mon Amour,

Muriel,

Last Year at Marienbad) and Chris Marker (

La Jetee).

Just from looking at their films, it's clear that these filmmakers have a quality about them that sets them apart from the other New Wave brats: a tendency to think outside of the box and use cinema for truly original, even experimental exercises. Resnais' Hiroshima, Mon Amour and Marienbad have been highly praised as landmarks in cinematic grammar, as has Marker's La Jetee, which famously uses still photography to tell its story to great effect. Cléo From 5 to 7 also uses film form in a unique way: by closely following its protagonist, the eponymous pop singer Cléo (Corinne Marchand) in real time for an hour and a half as she journeys to different parts of Paris and meets various people. This is a creative way for the audience to become familiar with its at-first self-centered protagonist (who is awaiting the results of a medical test for cancer) and to see the city of Paris from its streets, taxis, buses, cafes, parks and a plethora of other perspectives, making the film just as much a delightful ode to flanerie as it is a fascinatingly made character study.

While Varda certainly has her differences from the Truffaut-Godard group, Cléo is most definitely a New Wave film. Like Breathless and The 400 Blows, it showcases both the city of Paris and its actors in striking black-and-white compositions (though the opening credit sequence, which focuses on a tarot card reading, is partially shot in color, contributing yet another stylistic oddity of the film). There is also the same strong sense of camraderie in it as in other New Wave films: Jean-Luc Godard, Anna Karina and Eddie Constantine all show up for cameos at one point, and the famed French composer Michel Legrand (who provided memorable scores for A Woman is a Woman, Band of Outsiders and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg as well as Cléo) is given a fairly substantial role as one of Cléo's collaborators. Indeed, this film is a most worthy entry in the new Wave canon, and easily fits alongside other cinematic masterworks from the period such as Vivre Sa Vie, Jules and Jim or any of the other films previously mentioned.

This year, Varda will be visiting the Toronto International Film Festival to present her new documentary, Les Plages d'Agnès, and speak about La Pointe courte, her first film (made in 1954), which many consider a key starting point for the French New Wave. I'll be going to the screening of the latter film, and I simply can't wait to see both it and the remarkable artist behind it in person.

This year, Varda will be visiting the Toronto International Film Festival to present her new documentary, Les Plages d'Agnès, and speak about La Pointe courte, her first film (made in 1954), which many consider a key starting point for the French New Wave. I'll be going to the screening of the latter film, and I simply can't wait to see both it and the remarkable artist behind it in person.

Also, I'll be taking a trip to France in a little less than a month (my first time there, and I can't wait), and among the many cinematic pilgrimages that I plan to make (most of the classic French film locations I want to visit come from Amelie and Breathless), I hope to follow in Cléo's footsteps and retrace her route through the city as seen in this film. That, along with seeing Varda at TIFF, is a dream come true for any fan of the French New Wave or Varda.

In closing, this is a wonderful film that comes highly recommended from a longtime fan who fell in love with it at first sight; here's hoping the same happens for you.

This year, Varda will be visiting the Toronto International Film Festival to present her new documentary,

This year, Varda will be visiting the Toronto International Film Festival to present her new documentary,